If you’re lucky enough to be flying with an autopilot, or if you’re dreaming about one day having an autopilot, then the term “flight director” is probably going to be in your vocabulary at some point. At first glance both of these terms sound similar, if not interchangeable, but they are actually separate things though they work closely together. So what’s the difference between an autopilot and a flight director?

An autopilot actually moves the aircraft’s control surfaces to change the aircraft’s attitude, heading, and altitude, whereas the flight director calculates the desired attitude based on what’s programmed into the autopilot and displays that desired attitude on the attitude indicator.

In other words, the autopilot actually controls the aircraft, and the flight director does the calculations to determine the desired flight path and can usually display this information to the pilot. Another way to think about it is that you can engage the flight director and still fly the aircraft manually and follow the attitude recommended by the flight director, all without ever activating the autopilot. More on this later.

As with most things, a picture is worth a thousand words and so let’s get into more detail along with the use of some imagery.

What’s the difference between an autopilot and a flight director?

As mentioned above, it’s important to remember that while frequently used in tandem, the autopilot and flight director are actually two separate things.

The FAA’s Advanced Avionics Handbook is a wealth of knowledge on this topic, particularly Chapter 4 which covers Automated Flight Control. I think they summarize the concept very well:

“Many advanced avionics installations really include two different, but integrated, systems. One is the autopilot system, which is the set of servo actuators that actually do the control movement and the control circuits to make the servo actuators move the correct amount for the selected task.

The second is the flight director (FD) component. The FD is the brain of the autopilot system.

Most autopilots can fly straight and level. When there are additional tasks of finding a selected course (intercepting), changing altitudes, and tracking navigation sources with cross winds, higher level calculations are required.

The FD is designed with the computational power to accomplish these tasks and usually displays the indications to the pilot for guidance as well.

Most flight directors accept data input from the air data computer (ADC), Attitude Heading Reference System (AHRS), navigation sources, the pilot’s control panel, and the autopilot servo feedback, to name some examples.

The downside is that you must program the FD to display what you are to do. If you do not preprogram the FD in time, or correctly, FD guidance may be inaccurate.”

Excerpt from Chapter 4 of the FAA Advanced Avionics Handbook

The autopilot does the actual moving of the airplane, whereas the flight director is the brains of the operation and makes all of the computations to determine what the aircraft’s attitude needs to be.

Additionally, and importantly, it mentions above that the flight director usually displays indications to the pilot for guidance as well. It won’t always. Let’s go through some examples of autopilots and flight directors to better understand the spectrum and see how they can work in conjunction yet serve distinct functions.

Autopilot

The autopilot (curiously sometimes referred to as “George” – see below for why this is) actually controls the airplane when it’s engaged. Autopilots come in all kinds of forms with various features.

Some only control a single axis of flight (like roll), whereas others control multiple axes (roll, pitch, and yaw) and even the throttle (Full Authority Digital Engine Control, or FADEC).

But the thing to remember is that the autopilot itself actually controls the airplane (or part of it, anyways). It isn’t doing much of the thinking, but more of the actual control inputs to fly the airplane. If you’ve ever heard the autopilot referred to as “George”, here are two prevailing reasons why:

If you haven’t already, we highly recommend you subscribe to the Airplane Academy YouTube channel! We are investing a lot of time and resources into documenting adventures, sharing lessons learned, and answering other aviation FAQs. Subscribe and sign up for notifications so you never miss our weekly video!

Autopilots have varied greatly in design over the years, both in features, user interface, and sleekness (as with the rest of avionics technology).

Pictured: A-3A Autopilot from the mid-1940’s used on American military bombers. It integrated the actual vacuum system (hence the suction gauge at the top) and was designed to maintain level flight. Aileron and Elevator trim knobs would help the pilot make adjustments based on wind and aircraft loading and remove pressure on the control servos.

Pictured: An S-Tec 30 autopilot (this is the one that I have in my Cessna 182 currently) that has features for altitude hold, as well as heading and navigation modes. This particular model is incorporated into the turn coordinator and engaged by pushing the button on the upper left (that says “push mode”) to cycle through the different autopilot modes.

Because it will compute the attitude for desired headings and navigational courses, and make adjustments based on data from other systems onboard the aircraft (such as wind correction angles), this very much has a flight director inside of it.

It’s worth noting however that there is no flight director information presented to the pilot about the desired attitude. Even though the autopilot interface is embedded within the turn coordinator housing, don’t mistake the turn coordinator for the flight director. It is just displaying typical turn coordinator information and nothing about the desired flight path of the aircraft.

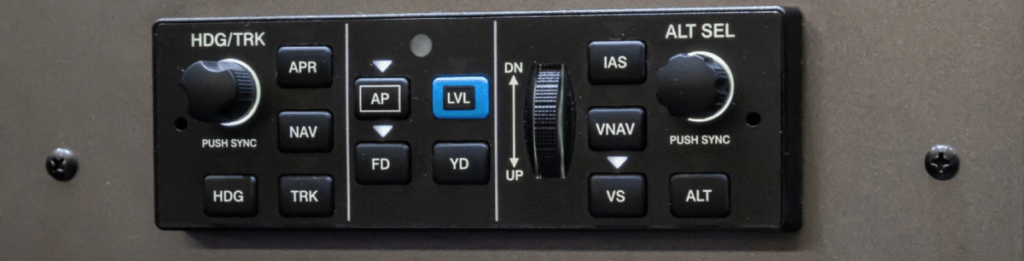

Pictured: GFC 500 autopilot. This is a more advanced autopilot (Garmin GFC500) with a lot of features, including VNAV (vertical navigation) and vertical speed controls, altitude changes and leveling, approaches, and the like.

The annunciated “AP” button means that the autopilot is engaged, which means it is actually controlling the airplane based on the information it is receiving from the flight director.

Unlike the S-Tec 30 above, this unit is designed to be able to display desired attitude information from the flight director to the pilot through an attitude indicator or a PFD (Primary Flight Display).

Notice the annunciated “FD” button with the white arrow above it – this means that the flight director is activated and displayed on the PFD (primary flight display) that it is connected to a Garmin G5. We’ll show this in a minute so you get the full picture.

All of these examples to say, while models and features vary, the point to remember is that the autopilot is what actually controls the aircraft when engaged.

Flight Director

The flight director on the other hand, doesn’t actually control the aircraft. It calculates and usually displays the desired attitude of the airplane to reach the targeted heading and altitude programmed into the autopilot.

In other words, the flight director is a calculation tool for the autopilot to know what to do, as well as usually visually represent where the airplane is going to go when the autopilot is turned on (or where you should hand fly it if you choose to engage the flight director but not the autopilot).

Going back to the GFC 500 autopilot, here is the full picture of the actual autopilot unit and the Garmin G5 PFD to which it is connected:

The color is a little hard to see, but if you look closely at the yellow chevron on the attitude indicator, you’ll notice that there is an overlapping magenta (it almost looks white in this photo) chevron on the top and sides of the yellow chevron. This is the flight director indicating the desired attitude of the airplane.

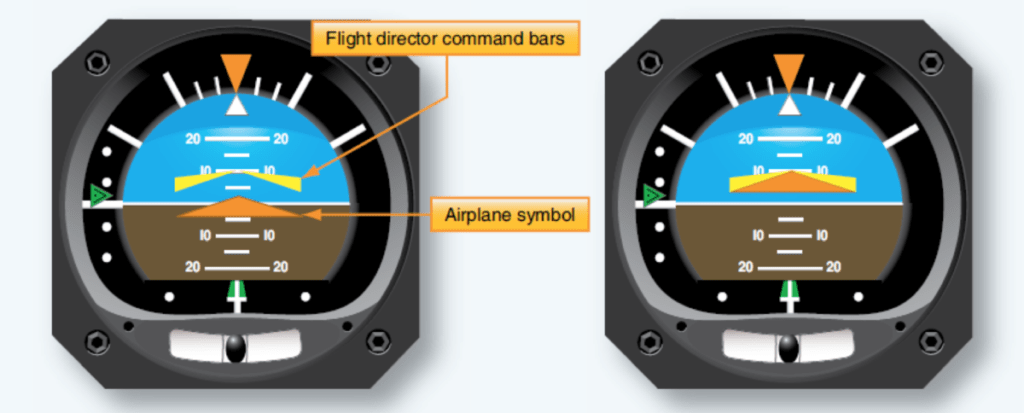

Here’s another example of a flight director that’s a little easier to see:

In the above image, while in level flight (the image on the left) you program a higher altitude into the autopilot and activate the flight director. The yellow “command bars” will appear on the attitude indicator and show you what the new desired attitude of the airplane is in order to fly to the higher altitude programmed into the autopilot.

Often you can toggle between different rates of climb or desired climb airspeeds and the flight director will compute and update the desired attitude accordingly.

If you then engage the autopilot, the aircraft’s attitude will then go fly what’s shown on the flight director. While designs vary, and in this instance you are exactly on target with the flight director when the orange triangle (the aircraft) is “filling in” or adjacent to the yellow chevron (as shown on the right).

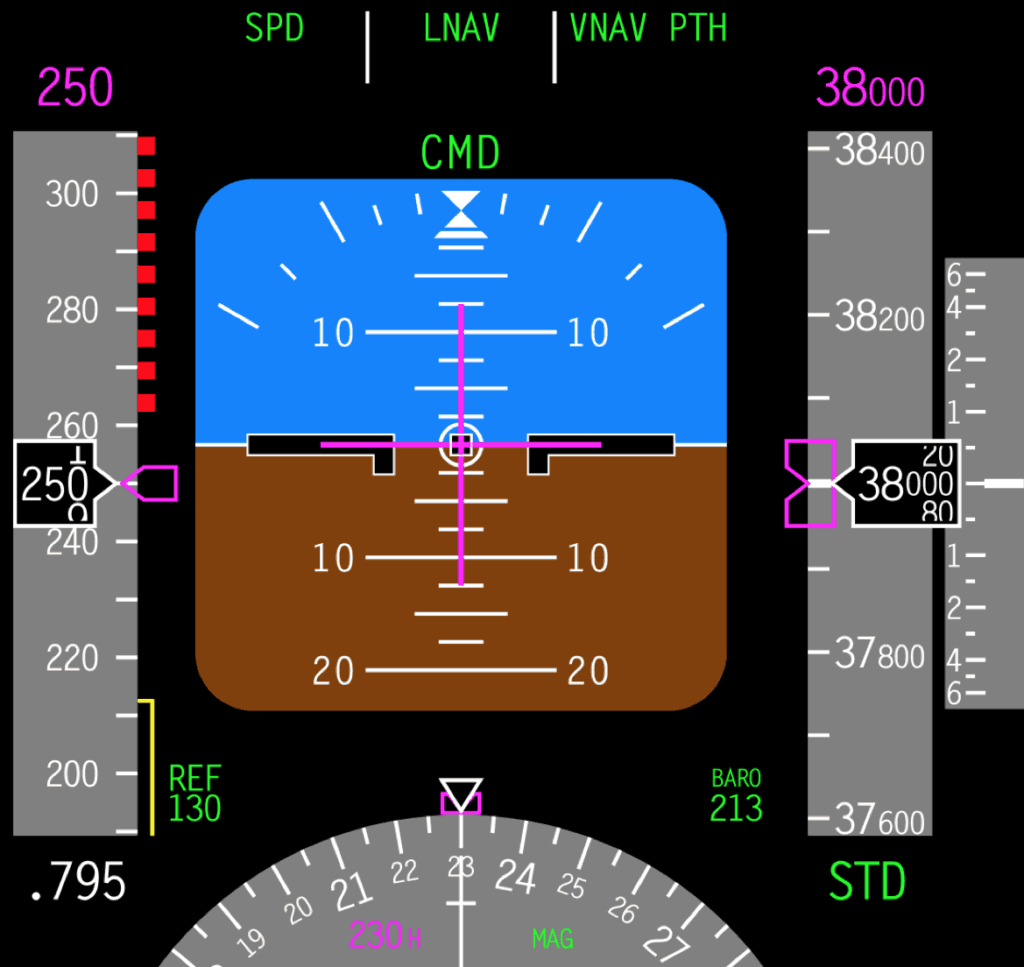

Here’s another example of a flight director displaying information, but this time in the form of lines instead of triangles and chevrons. The flight director interface will vary across avionics suites but the intent is the same.

The Flight Director Can Direct You OR George

One last interesting and helpful feature of the flight director is that if it has a visual display feature, you can engage just the flight director but not the autopilot if you so choose. So if you are planning on hand flying the aircraft but still want a visual reference for the desired attitude of the aircraft, engaging the flight director can be an extremely useful tool.

One example might be making a VFR departure at night, and you want to perform the climb out without the autopilot. Depending where you are, night VFR might as well be IFR because without ambient light it is very easy to lose reference to the ground. Engaging the flight director will give you a target on the attitude indicator to fly.

Or if you are hand flying an instrument approach, you can activate the flight director but leave the autopilot off. If you fly the command bars of the flight director, it will take you all of the way to the runway. You can’t activate the autopilot without activating the flight director, but you can activate and display the flight director without activating the autopilot.

Conclusion and Related Reading

One of the biggest factors of aviation safety is the situational awareness and workload of the pilot. The autopilot and flight director are two tools that can make a material improvement in the safety of your flight.

Even if you don’t have a visible flight director, the autopilot is still incredibly useful, but as you’ve seen above the visible flight director takes situational awareness to another level when understanding the desired flight path.

Being able to engage a flight director before you engage the autopilot will also provide confirmation that you’ve set up your autopilot correctly before you actually let it do the flying, because you can visualize and confirm the desired attitude based on the settings you gave it.

Here are a few other related articles on Airplane Academy for continued reading: