Instrument flying can take significantly more pre-flight planning than easier VFR days where you just show up and go. Not only do you need to plan any applicable departure and or arrival procedures, as well as the approach into your designation airport, you also need to take into consideration whether or not you need to file an alternate airport in case the weather at your original destination is below minimums.

To take things a step further, there are also alternate minimums you need to consider when planning if you need an alternate, and what airport that alternate will be. So, what are alternate minimums when flying IFR?

Standard alternate minimums require the forecasted conditions at the time of arrival be at least 2 miles visibility and at or above 600 foot ceilings for precision approaches, or 800 foot ceilings for non-precision approaches. For safety, some airports have non-standard alternate minimums that supersede these requirements.

Technically you can file an alternate at an airport without an instrument approach, but the forecasted conditions at the time arrival must allow for descent from the MEA (minimum en route altitude), approach, and landing under VFR.

In this post, we’ll elaborate on standard and non-standard alternate minimums, how to tell if an airport has non-standard alternate minimums, practical considerations for choosing an alternate, and some real-world examples.

When do you need an alternate in the first place?

Let’s start by briefly revisiting when you need an alternate in the first place. For safe flight planning, the FAA wants to ensure that if the forecasted weather conditions of your destination don’t meet a certain threshold that you have an adequate “plan B” that isn’t putting you in an unreasonable situation. Ideally this “plan B” will a more manageable weather situation than your “plan A”, in order to manage your stress level and also ensure you always have a safe means of concluding the flight.

In other words, you can try an approach to minimums at “plan A” airport, and if you can’t complete the approach, you already have a “plan B” airport in mind that has better weather and you know you’ll be able to get in.

Per 14 CFR 91.169, for aircraft other than helicopters an alternate airport is not required in an IFR flight plan if “for at least 1 hour before and for 1 hour after the estimated time of arrival, the ceiling will be at least 2,000 feet above the airport elevation and the visibility will be at least 3 statute miles.”

If you read the entire regulation, they are kind of presenting it in a double negative fashion. Said another way, the regulation reads that you must file an alternate if the forecasted conditions of your destination between 1 hour before and 1 hour after your estimated time arrival the forecasted have a ceiling below 2,000 feet or the visibility to be less than 3 statute miles.

This is commonly known as the “1-2-3 rule”. Plus or minus 1 hour from arrival, ceilings at least 2,000 feet and visibility at least 3 miles.

Easy enough.

So that covers when you need to file an alternate. But what about requirements for the alternate?

This is where alternate minimums come into play and are a very important part of flight planning, both from a regulatory standpoint but more importantly a safety standpoint.

What are alternate minimums?

As mentioned above, the point of an alternate airport is to ensure that you always have a viable “plan B” that is reliable so that you don’t get stuck when “plan A” doesn’t work. If the weather is well below forecasted and well below minimums at “plan A” airport you can have a backup option that is less stressful. Sure, it might be less convenient to not land where you hoped to with “plan A”, but it gets you on the ground safely.

To ensure that your alternate airport (“plan B”) is a reliable choice, the FAA has regulations on what the weather must be by the time you reached that alternate airport. They don’t want you to choose an alternate that has potentially the same or even worse weather than your original destination, so the requirements for an alternate airport provide a buffer. These are referred to as “standard alternate minimums”, which implies that there are also “non-standard alternate minimums”. The standard alternate minimums will apply to every airport, while non-standard varies from approach to approach.

Standard Alternate Minimums

14 CFR 91.169 reads that IFR alternate airports must be forecasted to have at least the following conditions at the estimated time of arrival at the alternate airport:

- For a precision approach procedure: Ceiling 600 feet and visibility 2 statute miles

- For a non-precision approach procedure: Ceiling 800 feet and visibility 2 statute miles

This means that even if the alternate airport you’d like to choose has an ILS approach (precision) with a DA of 200 feet, you cannot file it as an alternate unless the forecasted conditions at the time of arrival are at least 600 feet and 2 miles visibility.

Again, I think what the FAA is trying to do here is ensure that you aren’t getting yourself into a bind by filing your destination and alternate airport both at airports that have forecasted conditions well below minimums and you run out of available options mid-flight.

Sometimes in order to find forecasted weather that meets these standard alternate minimums means selecting an airport that could be 100 or more miles away if there is widespread IFR across the region. Don’t forget that this will impact your fuel requirements as well, as the IFR fuel requirement in 91.167 mandates that you can fly to your destination airport, then to your alternate airport (if one is required), plus another 45 minutes at “normal” cruising speed.

Referring to these as “standard” alternate minimums implies that there are “non-standard” alternate minimums (which there are). Let’s cover those next.

Non-Standard Alternate Minimums

Keeping the 600-2 and 800-2 standard alternate minimums in mind, there is one more step you need to take in your flight planning and that is to see if any non-standard alternate minimums might apply to your alternate airport or particular desired approach.

The concept behind non-standard alternate minimums is to provide another layer of safety. There are a host of reasons an airport or approach could have non-standard alternate minimums, but the way you can tell is by looking on an approach plate and looking for an inverted triangle with an “A” in it.

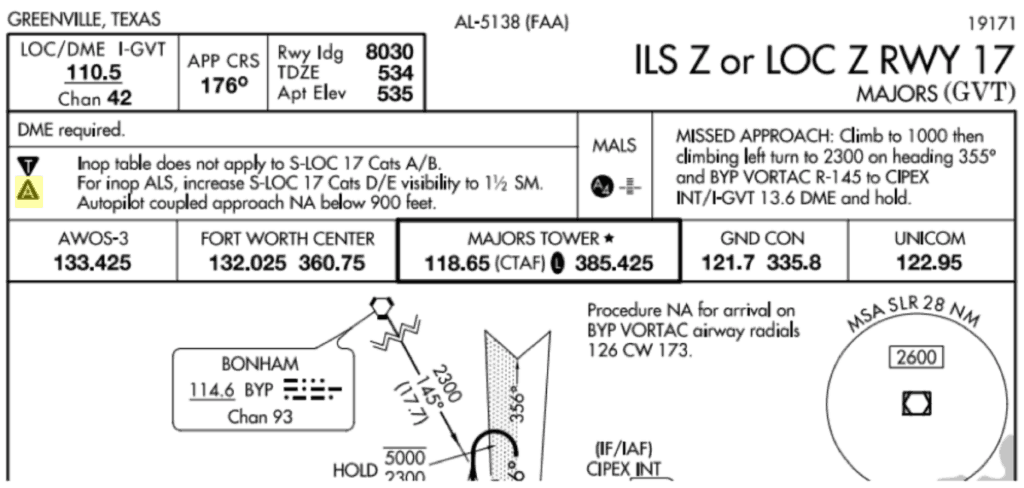

Let’s take Greenville Majors airport (KGVT) for example. The ILS Z 17 approach plate is as follows:

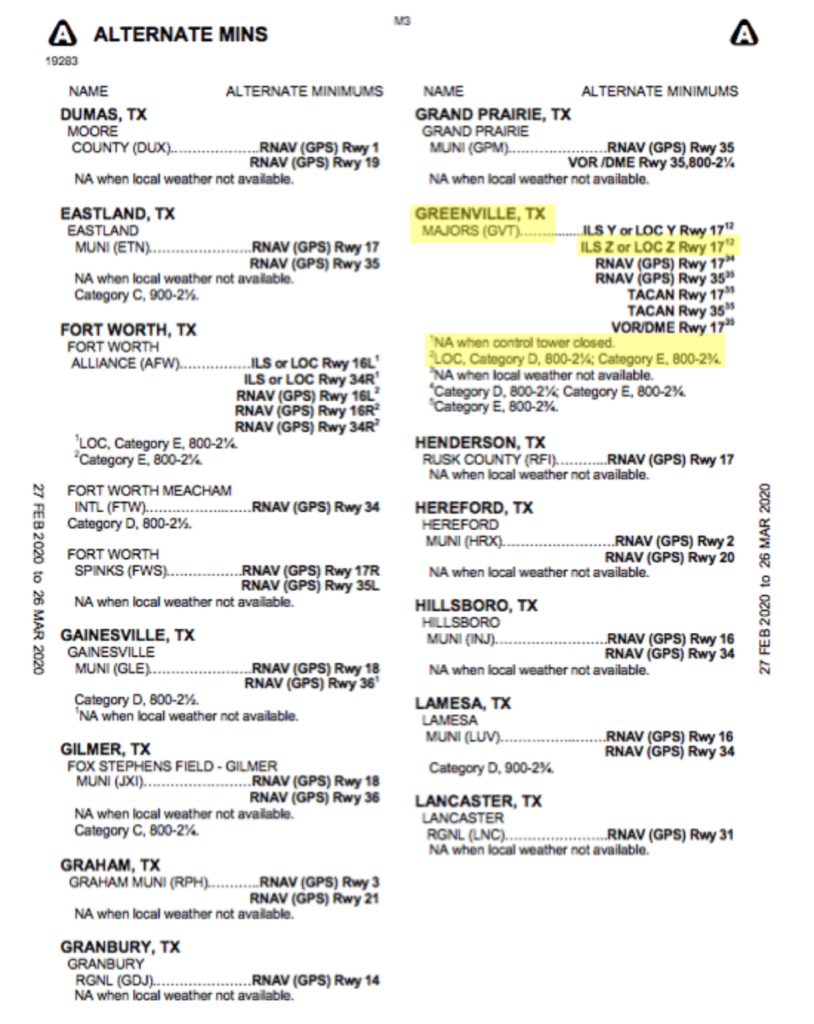

The “A” symbol indicates that alternate minimums apply to this approach. We’d then need to go look in the alternate minimums listing for that set of instrument approach procedure charts (back when it was all on paper, it would be at the very back of the booklet).

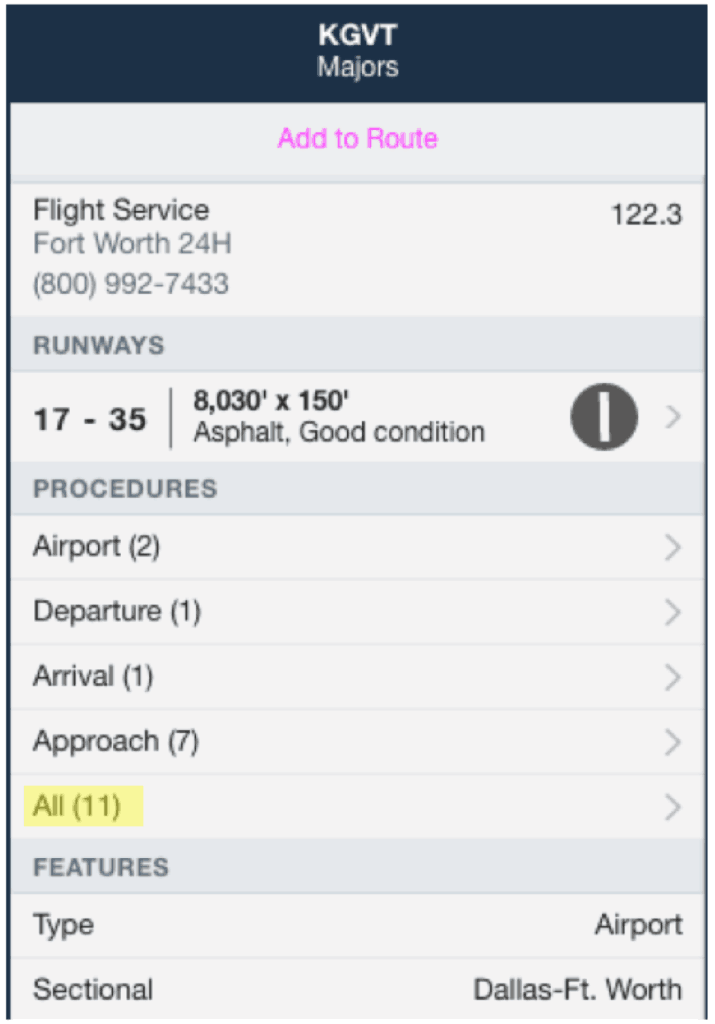

You can view this in ForeFlight by tapping on the airport, and instead of selecting “Approach”, select “All” which is likely the option right below it (you can also select “Arrival”).

Then select “Alternate Minimums”. On this page, we can scroll down to where Greenville is listed and look at what restrictions apply to our ILS Z 17 approach.

As you can see, this approach is not available when the control tower is closed. For the localizer approach, if we were flying an aircraft that classified in Category D or E for approach speed, the minimums are 800 and 2 1/4. The forecasted weather at arrival would need to meet that minimum in order for us to use it (if our aircraft was in that category). Either way, it isn’t available to be used as an alternate when the tower is closed, so we would need to look up the hours of operation for the tower and check that against our arrival time.

Some approaches might not be available when local weather is not reported. Or they might simply increase an MDA if you’re using the altimeter setting from a neighboring airport. Occasionally airports will use the weather information from a nearby airport for certain hours of operation or for other reasons. In that case, you’d need to see whether or not you’d have local weather at the time of your arrival to know whether or not it was a viable alternate.

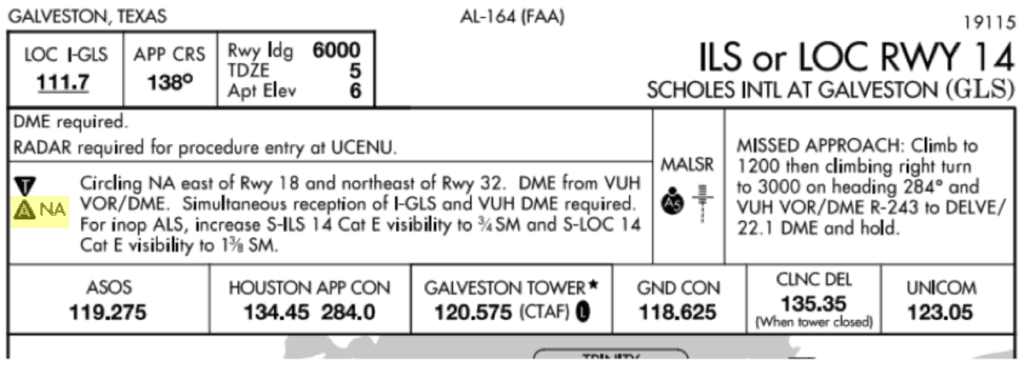

In other cases, certain approaches aren’t available at all as an alternate no matter the conditions (though other approaches at that same airport might not have the same restriction). If so, there would be an “N/A” next to the alternate minimums symbol on the approach plate. The ILS 14 at Galveston (KGLS) is an example of this:

All of this to say, there are different reasons that the FAA has put non-standard alternate minimums on various approaches, but the important thing to remember is that when planning your IFR flight you need to be sure to read the approach plates of all anticipated approaches to understand all of the implications for that flight.

Use of GPS Approaches

As of this writing, for WAAS-enabled GPS units, you can now have the destination and alternate both be an RNAV approach. However, non-precision approach minimums (800-2) would apply to qualify as your alternate, and flight planning must be based on flying the LNAV or circling minimums (and not an LPV, for example). You can read more about this in AIM 1-1-18 paragraph C, subsection 9, paragraph A.

The FAA seems to be slowly making these regulations more GPS-friendly but there is still room to grow in my opinion.

For non-WAAS GPS units, the old regulation still applies to where you can have a GPS approach be either your primary or alternate airport approach, but not both. See AIM 1-1-17 section on “GPA Instrument Approach Procedures” paragraph C for more on this.

Practical Suggestions for Choosing an Alternate

Sometimes planning out the IFR flight plan can lead you down a rabbit hole of finding particular approaches that work with your aircraft’s equipment, fuel and range requirements, and forecasted weather. Because that can be an iterative process to decide on the right alternate airport, here are some practical considerations to keep in mind:

Approaches / Equipment

Based on either the equipment onboard, your personal preference, or maybe even the non-WAAS GPS nuance mentioned above, the types of approaches at available airports will be a large deciding factor in your alternate options. Hand in hand with this consideration is the weather.

Weather

Obviously the weather at the alternate airport selection will need to meet the standard or non-standard (if applicable) alternate minimums, but don’t forget to take a larger view of the weather in general. Where is it forecasted to get better? Where is the front coming from and where is it expected to lift? An airport that appears to have reasonable weather might be forecasted to get worse as the day goes on because of a passing front, so make sure to take trend information into consideration.

Runway Lengths

I doubt there is an airport with an instrument approach that has too short of a runway for my Cessna 182, but as you fly bigger birds, runway length absolutely becomes more of a factor.

Distance & Fuel Requirements

As a reminder, you need to carry enough fuel to reach your destination airport, then to the alternate airport (if applicable), plus 45 minutes at a normal cruise speed. The farther your alternate is, the more fuel you’ll need. If you have passengers and cargo to factor into the weight and balance as well, you might not have a very large radius of airports to choose from based on fuel requirements and its impact on the weight and balance of the aircraft. A farther airport might have drastically better weather, but you need to carry enough fuel to get there. A closer airport will mean less required fuel onboard, and will probably be more convenient for your passengers being diverted, but is the weather materially different at a neighboring airport? It’s all a balancing act.

Amenities

If you get diverted to your alternate, it’s good to look ahead and see what basic amenities are available. Short term benefits like a pilot’s lounge and a cozy FBO are definite perks while you wait out the weather. A courtesy car or taxi service to drive to a hotel in the event you really get stuck are a definite benefit, too. Don’t forget amenities for your aircraft either, such as fuel, tie-down, and hangar options as needed.

Alternate Advisor by ForeFlight

A really helpful tool if you use ForeFlight is their Alternate Advisor (available on all subscription plans). It easily aggregates information about nearby airport options and displays the anticipated weather, flight time, approaches available, runway length, and more, in an interactive view. It can save you a lot of time researching nearby airports one by one. Here’s an overview:

Real world example of alternate minimums

If you’d like a live example of walking through selecting an alternate, below is a pretty good video on the matter. Note that he does mention if the forecasted conditions are at 2,000 feet ceilings or 3 miles visibility you need an alternate, but the FAA regulations actually read that if they are AT or ABOVE those, you don’t need an alternate (only if they are below).

Conclusion and Related Reading

Alternate minimums (both standard and non-standard) are a very real part of IFR flight planning and can ensure there are plenty of options if landing at your destination airport is unsuccessful. While we always hope to land at the destination airport on the first approach, planning an optimal alternate airport is not only a matter of convenience, but more so a matter of prudence to ensure you always have a safe way of getting back on the ground.

Other related reading on IFR operations from Airplane Academy: