Frost is a thin layer of ice on a solid surface. It forms when water vapor above freezing comes in contact with a solid surface whose temperature is below freezing. Sometimes you may see this on your plane before departing on an early flight, and you may have wondered: “can I take off if there’s just a little bit of frost on the airplane?”

According to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), “frost the size of a grain of salt, distributed as sparsely as one per square centimeter over a wing’s upper surface, can destroy enough lift to prevent a plane from taking off.”

This a clear cut “no”. Even a little bit of frost can disrupt enough airflow that it can be detrimental to the airplane’s flight characteristics. But how exactly does this work aerodynamically?

What causes a wing to fly?

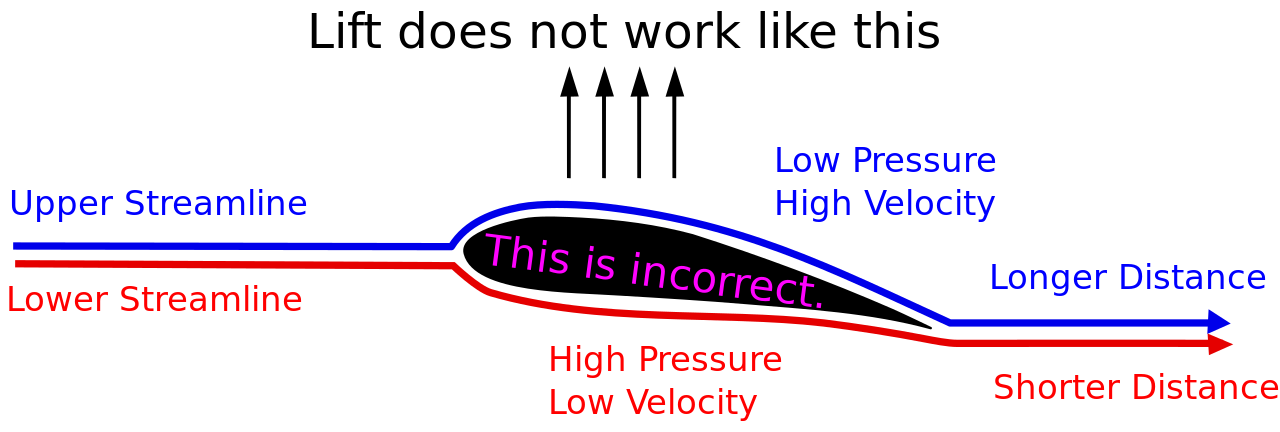

In 1738 Daniel Bernoulli published Hydrodynamica. In this book he discussed a principle of fluid dynamics, in which the speed of a fluid is directly related to its pressure: as speed increases pressure decreases. Fast forward a couple hundred years later and we have aviation.

In flight: wings are shaped so that the air (a fluid) flows over the wing faster, resulting in low pressure. The high pressure underneath the wing seeks out the low pressure on top, and pushes the wing up.

If the top of the wing has frost or ice on it, the air won’t be able to flow as quickly and won’t be able to create a low pressure on top, overall reducing the amount of overall lift.

Additionally, frost adds drag, and more lift must be created in order to overcome the drag, but lift is exactly what the wing loses when it has frost on it. It’s a vicious snowball effect, pun intended.

Exactly how much frost is too much?

Remember in Kindergarten when you would do projects involving glue? Your teacher would always caution against over-excessive usage with the all-familiar phrase “a dot does a lot.”

Well, that idiom seems to come in hand in this situation. Pilots are often too keen to stretch the boundaries, but when it comes to ice on the wings, it’s better to be overly cautious.

As we mentioned earlier, the NTSB says that “frost the size of a grain of salt, distributed as sparsely as one per square centimeter over a wing’s upper surface, can destroy enough lift to prevent a plane from taking off.”

Furthermore, according to the FAA’s Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PHAK), “An aircraft must be thoroughly cleaned and free of frost prior to beginning a flight… Frost disrupts the flow of air over the wing and can drastically reduce the production of lift. It also increases drag, which when combined with lowered lift production, can adversely affect the ability to take off.”

Let that settle in. This means that even the most miniscule amount of frost can be such a hazard you may not be able to fly. Or even worse: you may get out of ground effect, only to find out the control surfaces don’t operate efficiently.

Care to guess what happened when you stall and can’t recover? In simple terms, you are no longer flying, you are now falling.

When to Look for Frost

At the time of this writing, most places in the U.S. are still experiencing a lingering summer, as the days seem to retain heat the same way a pilot retains his advice to “aviate, navigate, communicate.” But just as your instrument knowledge starts to fade, these hot days will soon fade to cold, crisp mornings. With this change of seasons comes new obstacles for the seasoned aviator.

So what causes this subarctic material to form over the wing?

Pulled straight from the trusted PHAK, “Dew and frost form on cool, clear, calm nights, when the temperature of the ground and objects on the surface can cause temperatures of the surrounding air to drop below the dew point (tight temperature-dew point spread). When this occurs, the moisture in the air condenses and deposits itself on the ground, buildings, and other objects like cars and aircraft. This moisture is known as dew and sometimes can be seen on grass and other objects in the morning. If the temperature is below freezing, the moisture is deposited in the form of frost. While dew poses no threat to an aircraft, frost poses a definite flight safety hazard.”

Where would you see frost on the airplane?

Keep in mind sometimes dew may form and as the night matures, colder temperatures can cause the dew to turn to frost. The best way to check if it’s frost on the wing is to run your hand along the leading edge and feel for it.

If you fly a high wing airplane, such as the ever-popular Cessna 172, make sure you check the top of the wing as well. Anywhere there’s frost should make your flight an immediate no-go.

One trick for checking frost on top of the wing is to taxi over to the fuel pump. Use the ladder at the pump to get above the wing to ensure an accurate visual on the topside of the wing is done.

You see frost, now what?

The air bites at your nose. You’re ready to take off to meet the boys for your weekly $100 hamburger, and you find frost at the top of the wing. What should you do?

The most common method for removal, and cheapest, is to simply position the plane in sunlight and let the warmth melt off the ice. Just know this may take somewhere close to an hour and is a slow fix.

If you’re extra prepared, position your plane into an “early sunlight” parking spot the night before so the plane can become bathed in sunlight as soon as the sun breaks the horizon.

Another common method is to use de-icing solution. Certain FBO’s will have this solution on hand, but know that most charge by the gallon and this stuff is not cheap. It’s also not that common in GA flying, especially if you reside in the southern US.

If you have a friend with a warm hangar, you have another option. Just put your plane in the hangar the night before and stop the frost from forming in the first place.

Lastly, some pilots believe it’s best to carry a 15 foot or so length of rope to drag down the wing. This has been brought up in various flight forums because it’s said that the friction from the rope will help melt off any ice or frost. Just remember to use a gentle material of rope, especially if your plane is old or worn.

It’s better to be on the ground, wishing you were in the air

In the end, the best method to ensure you won’t get in any frost-related accident is to stay on the ground. That morning flight can wait. The $100 hamburgers will be there tomorrow.

Nothing is more dangerous than “take-off-itis” and having just a small bit of frost on the wing, and chancing it, is a fast way to end up in an NTSB report.

Don’t believe me? Do one quick search for “frost” or “ice” on the NTSB website and you will find a slew of reports that are littered with the same tidbit of wordage, where a pilot took off with ice on their wings and instantly became a test pilot.

It all comes down to poor decision making. Don’t chance it, play it safe. Whatever you need to do, wait it out. Fly tomorrow when it’s warmer and be prudent in your decision making. So much of being a pilot is having smart and disciplined decision making skills, and flying with frost on the airplane is NOT a good idea.

Be patient and yield to mother nature. Live to fly another day. And although the saying may be corny, it’s truly a good day when you can honestly say “it’s better to be on the ground, wishing you were in the air, than in the air, wishing you were on the ground.”

Other Considerations During Frost Conditions

Anytime you are dealing with near or below-freezing temperatures, you need to be extremely careful with airframe icing and also carburetor icing (if your engine is carbureted). We’ll be releasing an article on airframe icing in the future and will link it here, but in the meantime you can see our article on carburetor icing and its causes, indications, and remedies.