When looking at your VFR sectional chart, you may have noticed a few airports around the country surrounded by a unique type of airspace know as a TRSA. What is a TRSA?

TRSA airspace, meaning Terminal Radar Services Area, consists of areas around especially busy class D airports where ATC provides traffic separation with the use of radar. Though typically busier than other class D airports, these airports are not busy enough to have been classified as Class B or C airports.

TRSAs are often described as being “optional Class C” airspace. They function and provide services just like Class C airspace, but participation is optional for VFR pilots.

As pilots, it’s our job to safely navigate any type of airspace we might come across. With that in mind, let’s discuss some of the special features of TRSA airspace that you will need to know.

What is TRSA airspace?

First of all, let’s tackle some legal definitions and then we’ll discuss practical information you need to know about flying into TRSAs.

TRSAs or Terminal Radar Services Areas, are different from other types of airspace you may be familiar with. Airspace in the United States is legally defined by 14 CFR Part 71, which you can read here.

If you read 14 CFR Part 71, you will notice that TRSAs are not mentioned even once!

They are classified as non-Part 71 airspace. Because TRSAs are not legally defined in the FAA’s regulations defining airspace, participation is optional for VFR pilots – more on that later in the article.

TRSAs have at least one Class D airport within their boundaries – where you will have to follow normal Class D rules (equipment, cloud clearance, communications, etc.). The TRSA also extends further and higher than the underlying Class D airspace.

This TRSA airspace is legally Class E airspace, therefore you will have to follow normal Class E rules.

What does TRSA airspace look like on the sectional chart?

If you are used to identifying Class B and Class C airspace on your VFR sectional chart, interpreting TRSA airspace will also be very easy.

The example below shows the relatively straightforward TRSA airspace surrounding Erie International Airport in Erie, PA.

Items relevant to the TRSA are highlighted in green. The TRSA is defined by the dark grey rings and dark grey floor and ceiling altitudes on the chart.

Within 5 statute miles of the airport, the TRSA extends from the surface up to 6000’ MSL as shown by the dark grey ring and the 60/SFC label.

From 5 to 10 statute miles of the airport, the TRSA extends from 2500’ MSL to 6000’ MSL over the land and 2300’ MSL to 6000’ MSL over Lake Erie.

Just like other types of airspace, TRSAs have variable shapes due to conflicting nearby airspace, instrument approach corridors, topography, or other factors unique to the local area.

What services are provided by TRSAs?

When you are in contact with TRSA controllers you can expect the same services provided by other approach control centers in U.S. airspace.

You will be assigned a distinct squawk code and be given traffic alerts when other planes are nearby you. The controllers may also assign you specific altitudes and headings to fly.

If you choose to participate in the TRSA, these altitude and heading assignments are mandatory.

As always, if the controllers instruct you to do something that you cannot safely comply with (for example, a heading that would steer you into a cloud while flying VFR), don’t hesitate to say “unable”.

Remember though, when operating under visual flight rules you are still ultimately responsible for avoiding other traffic. TRSA separation services are a helpful benefit but the responsibility to see and avoid ultimately lies with the pilot in command.

Where does TRSA airspace still exist in the U.S.?

TRSA airspace used to be more common than it is today. Many airports that used to operate under TRSAs have since been reclassified as Class C or Class B airports.

For example, KGRR, Gerald R Ford International Airport in Grand Rapids, Michigan used to operate under a TRSA but has since been reclassified as a Class C airport.

While TRSAs could be considered somewhat outdated, they still provide valuable services to pilots and exist in every part of the U.S.

At the time of this writing, 31 airports in the U.S. still have TRSAs. Some of the TRSA airports in this list could be reclassified as Class C airports.

28 markers are shown above, Andersen Air Force Base in Guam and Fairbanks International Airport in Alaska have been omitted. Two Class D airports operate under the same TRSA in the case of the Harrisburg, PA TRSA and the Macon, GA TRSA.

Some examples of popular airports with TRSAs include Palm Springs International Airport in California, Fairbanks International Airport in Alaska, and Erie International Airport in Pennsylvania.

How to Fly in TRSAs

What equipment do you need to fly into TRSA airspace?

Participation in TRSA airspace is optional for VFR aircraft. Pilots are under no obligation to contact the TRSA controllers when flying into a TRSA. Therefore, you do not need any specific equipment to fly VFR in TRSA airspace if you choose not to participate in the optional radar services.

If you do want the radar services offered by the TRSA, you will obviously need a radio (to talk with the controllers) – and that’s it.

If the airplane you fly doesn’t have a transponder or ADS-B, don’t be shy about still participating in the TRSA. The controllers can usually still see your aircraft with primary radar (more on that later).

However, if you want to land at the underlying Class D airport, you will need to follow Class D airspace rules.

Luckily, Class D airports don’t have very strict equipment requirements for flight operations. If you fly into the Class D airspace inside a TRSA, you need to establish two-way radio communications with the tower – so you need a radio. You do not need a transponder or ADS-B.

What communication requirements exist for TRSA airspace?

If you are flying VFR, you are not required to contact the TRSA airspace controllers at all if you are merely transiting the TRSA.

That being said, it’s a good idea to contact the controllers so they know where you are and can provide traffic alerts. In this way TRSA airspace functions just like the optional VFR flight following services offered by air traffic control.

If you fly into the Class D airspace inside a TRSA, you need to establish two-way radio communications with the tower.

If you are already talking to the controllers managing the overlying TRSA, they will hand you off to the tower frequency like a Class C approach control handing you off to the tower frequency. The tower will already be expecting your arrival, know your general location, and will use the same squawk code you got from the TRSA controllers.

If you choose not to participate in the TRSA, you can just contact the tower directly.

Just like flying into any other Class D airspace when you contact the tower, you should state:

- You have the current ATIS information (Alpha, Bravo, etc.)

- Your position

- Your altitude

- Your intentions (touch and go, full stop landing, etc.)

If you are flying IFR, you will already be in contact with air traffic control and the handoff to the TRSA will occur like any normal handoff between air traffic control centers.

Want more tips on communicating with ATC? See our article on 13 practical tips and tricks to improve your ATC skills.

What is the difference between Class C and TRSA airspace?

The most important difference between Class C and TRSA airspace is that participation in a TRSA is optional, while participation in Class C airspace is not optional. You will not break any rules if you fly directly into a TRSA without a transponder, a radio, and without talking to anyone.

If you try to enter Class C airspace without talking to the relevant approach control ATC, you will have violated controlled airspace and may face consequences.

Beyond the difference in mandatory participation, TRSAs and Class C airspace function similarly.

As a VFR pilot, you would first contact the relevant approach control (for example, SOCAL Approach for Palm Springs Airport is 135.27 Hz) and state your intentions. The TRSA will provide separation services and sequencing.

However, remember that when you are operating under VFR traffic separation is ultimately your responsibility – so keep up your scan (see and avoid!).

How do ATC radar services work in TRSA airspace?

Without getting too technical, TRSA services work the same as other approach control radar facilities operated by air traffic control. TRSA air traffic control and other ATC facilities can “see” your plane in two ways: primary radar and secondary radar.

Primary Radar

Ground-based radar facilities sweep the airspace and send radio signals toward the sky. When a large, reflective object (like a plane) bounces the signal back to the ground station, direction and distance can be determined by calculation of the speed of light travel time of these radio waves.

Ground-based ATC radar station. The lower dish is primary radar, while the flat upper dish is for secondary radar. Image Source

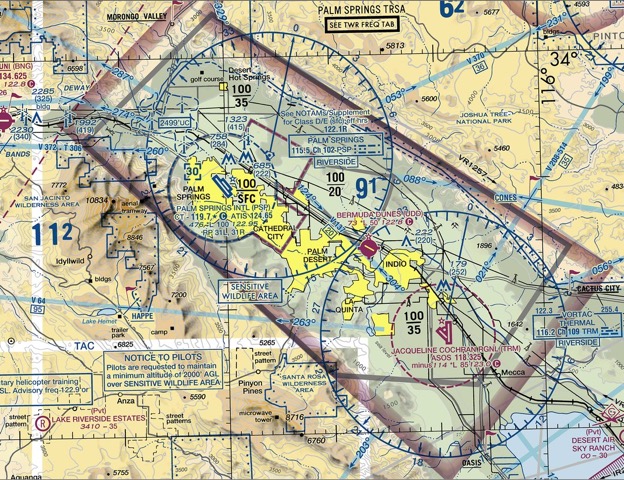

These radar facilities do not work through solid material like terrain. That’s why some TRSAs are shaped to the local terrain like the example below in Palm Springs, California.

The very high peaks of the San Jacinto Mountains to the south and the Little San Bernardino Mountains to the north block radar coverage and give the TRSA a more polygonal shape. This isn’t unique to TRSAs of course. You may have heard air traffic control indicate that you are too low for radar services. Terrain often makes it hard for you to be seen by ATC!

Secondary Radar

Primary radar is very accurate but has its limitations. For example, ATC can only see that “something” is being detected by the radar facility. There is no way to differentiate or identify different planes.

That’s where secondary radar comes in.

The transponder in your plane is integral to secondary radar. Secondary radar sends a radio frequency to your plane which is detected by your transponder. The transponder responds with a 4 digit code that is assigned by Air Traffic Control.

If you are in contact with the TRSA controllers, you will have been assigned a distinct 4 digit squawk code. If you decide not to participate in the TRSA, you should squawk 1200, the standard VFR squawk code.

The underlying Class D tower may or may not assign you a unique code depending on traffic volumes and ATC standard operating procedures at the airport.

TRSA Airspace Summary

In summary, TRSAs use radar to provide separation services for pilots operating around busy Class D airports. These services are voluntary, but recommended when operating in these congested areas. For all intents and purposes, TRSAs can be thought of as busy airspace that provides “optional” Class C airspace services.

Participation in TRSAs is optional, but strongly recommended. Remember that TRSAs exist around particularly busy airports. The radar services are in place to keep everyone safe.

Hopefully this article will help you next time you fly into a TRSA or help you provide a confident answer the next time an examiner tries to stump you with an obscure question on your VFR sectional chart!