Many have been taught throughout the years that operating an aircraft engine oversquare is a very bad thing. Engine monitoring technology and teaching knowledge has advanced and oversquare operations are not quite as mysterious as they once were.

Is operating an aircraft engine oversquare harmful?

Operating an engine oversquare is not harmful to an engine as long as the power settings are within the parameters outlined within the Pilot’s Operating Handbook or the Engine Operator’s Manual. Operating oversquare outside of these limitations can cause engine damage.

In fact, operating oversquare is desirable for many reasons and downright preferable. However, it is important to know what the tradeoffs are for oversquaree operations and weigh them against the benefits.

What is “operating oversquare”?

“Oversquare” refers to the ratio of the manifold pressure setting in inches of mercury being higher than the engine RPM setting in hundreds of revolutions per minute. For example, a power setting of 25” of manifold pressure and 2,300 RPMs would be oversquare.

A power setting of 23” of manifold pressure and 2,300 RPMs would be considered square, often pronounced “twenty-three square”.

A power setting of 23” of manifold pressure and 2,500 RPMs would be considered undersquare and would be pronounced “twenty-five twenty-three”.

What is bad about operating oversquare?

Many instructors over the years have warned that operating oversquare could cause almost immediate, irreparable, and catastrophic damage to the engine because the higher manifold pressure and low RPMs creates too much resistance on the engine.

The internal pressures resulting from feeding all of that fuel/air mixture into the cylinders while forcing the engine to turn very slowly due to the prop being at its most coarse pitch is akin to “lugging” a car engine by trying to accelerate from a standstill while in 5th gear.

Fortunately, the truth is not quite so dire. Even so, there is some danger to operating oversquare, but that really has to do with extremes.

For example, running the aircraft at full throttle while the propeller RPM is set to its lowest setting would not be good for the engine.

The good news is that as long as we are operating within the parameters specified in the POH or the engine’s Operator’s Manual, there is absolutely no harm in operating oversquare. In fact, there are many benefits to it!

What are the benefits to operating oversquare?

There are quite a few benefits to operating oversquare.

The first, and in my opinion most important, reason to operate oversquare is passenger comfort. The single largest contributor to cabin noise in our piston-powered aircraft is engine/propellor noise.

Reducing the RPM is the only way to reduce it.

I will almost always choose the lowest RPM setting for a given power setting that is allowed by the POH or engine operator’s handbook – especially if I have passengers.

It also stands to reason that a slower turning engine results in less wear and tear on the moving parts.

Typically, when the oil is changed, the filter is inspected for bits of metal that may appear due to internal friction. This appearance of metal in the filter is sometimes referred to as “making metal”.

Well, the slower the engine turns, the less metal that is made. That benefits owners and renters alike by allowing engines as much chance as possible to reach the expected time between overhauls.

Another benefit to oversquare operation is that it results in a much more efficient transfer of energy from the spark to the piston.

According to this 10/18/2018 article in AOPA Pilot written by Mike Bush, operating oversquare at lower RPMs allows more time between ignition of the fuel/air mixture and the exhaust valve opening. This results in less of the combustion going out the exhaust valve and more of it pushing the piston.

Speaking of Mike Bush, he has a fantastic (and highly regarded) book on aviation engines, aptly named “Engines”. You can check it out and get a copy here. Highly recommended.

Operating Considerations to Oversquare Power Settings

The first oversquare situation we encounter when operating is during the runup.

The throttle is advanced to something like 1,800-2,000 RPM, a mag-check occurs, and then the propeller is exercised. This is accomplished by moving the propeller control to full low RPM/high pitch.

We watch the RPM for the corresponding drop, look for the MP rise, and also watch the oil pressure gauge.

(Side note: for more info on this, see our article on why lower prop RPM causes higher manifold pressure.)

We also listen for the whoosh that takes place as the blades increase their angle of attack to take a much bigger bite out of the air.

The POH for the Beechcraft Sierra only requires that the propeller be exercised to obtain a 300-400 RPM drop and then the control can be returned to high RPM.

Accordingly, when flying the Sierra, pull the prop control back to get that drop and then quickly return it to its full forward position rather than letting it go all the way to a fully coarse pitch – that’s it.

There is no need to cycle it multiple times. Doing so only increases the wear and tear within the engine and also the prop governor.

In a multi-engine piston powered aircraft, the POH may call out the need for a feathering check. In this case, the propellor control is moved past the low RPM setting and back into the feather range.

It is vital to know that, if needed, the propeller will feather in case of an engine failure so that drag is reduced as much as possible.

However, in a single-engine aircraft, there is no need to sit there at run-up power with the propeller control pulled all the way back for an extended amount of time.

On takeoff, most aircraft regularly operate oversquare.

If you are operating within a few hundred feet of sea level, full throttle MP of 28”-30” is the norm. Since most RPM redlines are typically 2,5000-2,700 RPM, this creates an oversquare condition.

Some aircraft, like the Beechcraft Sierra C24R do not have any limitation on operating at full throttle and maximum RPM. This means that one could operate oversquare as long as the fuel supply holds out and be well within the operating limitations.

Later on, during cruise flight, a cruise power setting must be selected. This is likely our third chance to operate at an oversquare power setting.

Fortunately, there are two primary sources for information in regards to properly operating your aircraft’s engine; the Pilot’s Operating Handbook and your engine’s Operator’s Handbook.

Both will outline the approved power settings and the resulting performance.

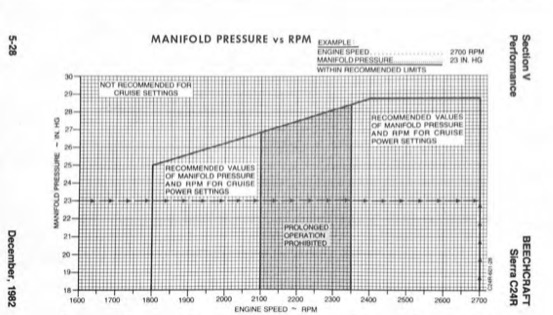

The Beechcraft Sierra’s POH offers up a “Manifold Pressure vs RPM” chart (pictured below) that clearly defines the recommended values and combinations of MP/RPM.

By referencing this chart, it is clear that operating at 2,400 RPM at manifold pressures of 28”+ falls within the “recommended values of manifold pressure and RPM for cruise power settings.

It is also a good idea to obtain the operator’s manual for the engine of the aircraft you operate. The operator’s manual contains a plethora of information about operating the engine – go figure!

Everything from power settings, leaning charts, to starting procedures are detailed within the engine operator’s manual.

Turbocharging and Operating Oversquare

Pilots operating a turbocharged aircraft operate oversquare more often than not during takeoff, climbout, and cruise.

This is because the turbocharger compresses the outside air on its way to the intake manifold. This causes the engine to perform as though it is at much lower altitudes than it really is.

That is the point of having turbocharging – developing full power all the way up to the limitations of the turbocharger.

This is otherwise known as the “critical altitude” and can be anywhere from 12,000’ to 20,000’ depending on the aircraft.

For example, the POH from a Cessna Turbo Skylane RG allows for the following power settings:

- Takeoff 31” and 2,400 RPM

- Cruise climb of 25” and 2,400 RPM

- 10,000’ cruise of 25” and 2,100 RPM

There are many intricacies involved in operating a turbocharged aircraft that do not apply to normally-aspirated aircraft. So, while it is not really an apples-to-apples comparison, it does provide a vivid illustration of how there are always exceptions to the “rules”.

Oversquare operation dangers: fact or fiction?

There is definitely truth to the idea that operating an aircraft outside of the published limitations is a risky endeavor. However, operating oversquare is not automatically a problem.

The fact that the MP number is higher or lower than the RPM is purely a result of the units of measurement. This is what makes over-generalizations like the dangers of operating oversquare so silly.

In fact, if we measured the air pressure within the intake manifold using the metric system, everything would be “oversquare” and it really would not even be a thing. For example, rather than a climb power setting of 25”/2,500 RPM, the power setting would be 847hpa/2,500 RPM. The oversquare generalization would not exist and we would have to rely on the POH for the correct power settings.

The only rule that applies to correct power settings is the one that says that the pilot must refer to the Pilot’s Operating Handbook and the Engine Operator’s Manual.

The POH and EOM are the only places that a pilot will learn which MP/RPM settings are acceptable and which are not.