Carburetor icing is a serious topic that affects nearly every pilot at some point in their training or flying career. A significant portion of piston-powered aircraft still use carburetors, and icing is one of their inherent operating risks.

So what is carburetor icing?

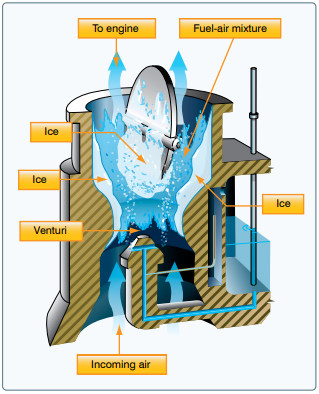

Carburetor ice forms when the air passing through the carburetor venturi mixes with vaporized fuel causing a large temperature drop within the carburetor. The moisture in the air can form ice, restricting the air and fuel flow to the engine and resulting in a partial or total loss of engine power.

Fortunately for us, the conditions that cause carburetor icing are fairly predictable and aircraft manufacturers have been nice enough to give us some tools we can use to combat carburetor icing. Every pilot should quickly familiarize themselves with the causes, signs, and remedies for carburetor icing.

What causes carburetor icing?

The carburetor is a time-tested, rugged, reliable way to mix fuel and air. As part of that fuel/air mixology, the air passes through a venturi as it is mixed with the fuel.

You may recall from discussions about Signor Venturi and his eponymous tube that as the air moves through the constriction, it speeds up and the pressure decreases. As pressure decreases, the temperature will drop.

When the temperature drops, the moisture within the air tends to transform from its gaseous state into water.

In addition to the reduction in temperature caused by the air pressure change, the vaporized fuel being introduced at that moment causes an additional temperature drop.

These two troublemakers (the cooling air and the vaporized fuel) result in a temperature drop that could approach 60 to 70 degrees fahrenheit. This can cause the air temperature to quickly fall below freezing and begin forming ice (even in very hot weather).

I’ll bet you didn’t realize that the carburetor also doubled as an ice maker! Here is a good visualization of carburetor ice from the PHAK:

Can carburetor ice form on hot days?

I referred to the vaporized fuel and low pressure air as troublemakers because they conspire together on what can result in carburetor icing. This is especially true on hot and humid days when icing is the furthest thing from an aviator’s mind.

Picture it in your mind for a moment…

You’re flying in the middle of August out of an airport near Houston, Texas. It’s almost 100 degrees fahrenheit outside. The only ice on your mind is the ice in the cooler waiting for you after your flight when it is time to do some hangar flying.

While the outside air temperature is 100 degrees, the venturi air and vaporized fuel are working together to lower the carburetor by 70 degrees. This means that even in very hot outside temperatures, the temperature in the carburetor could still be below freezing and capable of producing ice.

Couple that with the fact that you’re flying out of Houston and the relative humidity is likely off the charts, there is quite a bit of moisture condensing within that venturi and the interior of the carburetor (including the throttle valve) as the air cools.

This is the perfect recipe for carburetor icing that can catch pilots by surprise. Not to mention that this is happening during takeoff and landing – two critical phases of flight!

So, even on hot days, you need to always be cognizant of the threat of carburetor icing.

When is carburetor icing most prevalent?

According to the AOPA Safety Brief Number 9, the most prevalent carb ice conditions are when the air temperature is between 50 and 70 degrees fahrenheit and the relative humidity is more than 60%.

However, carb icing can occur in a much wider range of temps and humidity levels.

On the other hand, freezing temperatures alone do not present a threat without there being enough humidity from which the condensed water will freeze or temperatures so low that the fuel might freeze.

As was discussed in How Does Aircraft Fuel Not Freeze During Flight? it takes very, very low temperatures for Avgas to freeze. So, it is temperature and humidity that are what we, as pilots, are mainly concerned with – not fuel temperature.

What are the indications of carburetor icing?

Your first signs of carburetor icing will be a decrease of engine performance and likely engine roughness as the fuel/air mixture becomes less tolerable to your engine.

The specific decrease in engine performance will express itself differently in fixed and variable pitch (constant speed) propeller equipped aircraft.

If the aircraft you are flying has a fixed pitch prop, then the first sign of carb icing will likely be an RPM drop.

In constant-speed propeller equipped aircraft, a drop in manifold pressure is usually the first sign of carburetor icing since the prop governor is keeping the RPM’s constant. However, if you have the prop control full forward, you might also notice an RPM decline along with a manifold pressure decline as the first sign of carburetor icing.

Should you ignore this long enough, or if conditions are severe enough, the carburetor ice formation could block enough of the fuel/air mixture to cause an engine failure. This is why one of the first (or memory) items on the rough-engine or engine-failure checklist is to activate carb heat!

It’s worth noting that low power settings can hide the typical indications of carb ice.

The low RPM associated with a low or power-off descent, more common during training, can hide that initial RPM drop that would otherwise trip the carb-ice trigger in your mind.

When performing low-power operations it is therefore desirable to apply full carb heat during the maneuver and also occasionally apply some power to make sure it is there if and when you need it most.

How do I stop my carburetor from icing?

If you see that RPM or manifold pressure drop, or you believe that the conditions are ripe for carburetor icing, the first action to take is to apply full carburetor heat.

When you activate that control, the air entering the carburetor venturi will now be sourced from within the engine cowling rather than directly from outside air.

This alternate air (not to be confused with an “alternate air source” commonly associated with your static ports) intake is placed so that the air is significantly warmer than any outside air. This warmer intake air will prevent carburetor ice from forming, or even melt carburetor ice that has already started to form.

Utilizing carb heat does not come without a couple of considerations, though:

- Since that “heated” air entering the carburetor is much warmer and less dense, your engine now acts as though it’s at a higher altitude because warmer air is less dense. There will be a slight power loss associated with the introduction of carb heat.

- Carb heart will richen the fuel/air mixture, so additional engine leaning may be needed as appropriate.

- The air is not flowing through the air filter which is typically positioned just before the air enters the carburetor. The carb heat air is usually unfiltered. Think about that and consult your aircrafts POH or approved flight manual in regards to using carb heat on a contaminated runway or in heavy rain.

How long should I leave carburetor heat on when suspecting icing conditions?

Use carb heat for as long as you need it (and then maybe a bit more).

When you first apply carb heat, there’s a chance that the engine will get a bit rougher even after leaning the mixture a bit. This is likely caused by the melting ice.

That water-formerly-known-as-ice is now being ingested by the engine and making its way through the suck-squeeze-bang-blow process. Even us pilots know that water does not burn very well, so as it passes harmlessly through the cylinder and out the exhaust valves, the engine may balk a bit.

However, as the ice clears (it could be just a few seconds to minutes depending on the severity of the carb ice) everything should eventually smooth out.

If you feel like the conditions are particularly favorable to carb icing, it might be a good idea to keep that carb heat applied in an effort to prevent another round of carb ice build-up.

Just remember that you may need to re-lean the engine due to the new power power setting and richer fuel/air ratio. I cannot stress enough that you should consult your POH or AFM regarding prolonged carb heat use.

Now you know that carburetor icing is not what covers your A&P’s birthday cake. It is a very important phenomenon that can occur in a wide-range of flight conditions. We have a responsibility to be aware of carb ice and the remedies we have available to us at our fingertips.

Related Questions

Is there a way to know the carburetor temperature?

Carburetor temperature gauges are commonly found in aircraft when the induction system design is particularly prone to carb ice build up. These gauges measure carburetor temperatures and can be digital (JPI engine monitors) or analogue (Mid-Continent Instruments).

The analogue versions typically have a yellow band indicating the temperatures most likely to result in carb ice. Operation within that band without the use of carb heat is fine as long as the atmospheric conditions are not favorable to carb ice formation such as when in very dry air.

Should carburetor heat be applied when in airframe icing conditions?

Airframe icing only occurs when the outside air temperature is near or below freezing. If you are experiencing airframe icing, it is possible that the air filter could get covered with ice. By activating the carb heat control, the engine air is now coming from a location less susceptible to airframe icing.

Out of the abundance of caution, it’s also worth noting here when discussing ice that you should never take off with frost on the airplane. For more reading on this topic, see our article on airplane frost.